The quality that makes Lewes FC unique is simultaneously an honour and a scandal. In the summer of 2017, the Rooks, as they are nicknamed, became the first football club in the world to pay their women’s team the same wages as their men’s team. This laudable initiative, called Equality FC, reflected the club’s belief that, as Karen Dobres, a non-executive director in charge of women’s audience development says, “Football can be an engine for social change.” And yet, to the shame of the game as a whole, in the past two-and-a-half-years, no other football club in the world has followed Lewes’ lead.

That failure may be shocking but it is not surprising. Although football has invested in the latest technology, sports science and data analysis, culturally it remains a conservative industry, albeit with a small c. In many countries, women’s football was prohibited for years with those bans only being lifted in 1969 in England, 1970 in Germany and 1975 in France.

The fact that the biggest football clubs now generate so much money – Manchester United reported record revenues of £627m for 2018/2019 – encourages cultural conservatism and discourages risk taking. The rampant, relentless commercialisation of the game was one of the things that stopped Stuart Fuller, the Lewes’ chair and head of football, from watching his beloved West Ham United. Alienated by the money – and the ripeness of the language his young daughter was exposed to watching the Hammers – he started looking for another club to follow. When he came to Lewes, on a friend’s recommendation, he fell in love at first sight.

The management team Fuller belongs to have shown a refreshing willingness to innovate and experiment on everything from solar power to directors’ boxes (which have been repurposed as beach huts and made available to fans). Some initiatives – such as a workshop to promote chanting during games – sound a little eccentric but that reflects the community the club is owned by and at the heart of.

A burning passion

The county town of East Sussex, Lewes has a burning passion for bonfires. The custom of setting fire to effigies of famous figures every 5 November – and the fact that the town is home to seven (count ‘em!) bonfire societies – can be a culture shock for new residents, who may feel they have moved into The Wicker Man country. The Sussex town also has its own currency, the Lewes Pound, with the iconic bonfires featuring on the £21 note. The town’s most famous former resident is probably Thomas Paine (1737 – 1809), the philosopher, activist and author of The Rights Of Man, who is often described as the intellectual godfather of the American Revolution.

Even the name of the Rooks’ stadium, The Dripping Pan, is a source of intrigue. Some say the bowl-shaped arena was used to pan salt, others that it was a monastic fish farm. A more romantic theory suggests that it was created to be filled with water to stage mock sea battles.

Founded in 1885, Lewes FC, like many non-league clubs, ran into financial difficulties in the 2000s and was effectively rescued in 2010 when it was transferred from private ownership to community ownership. Today, it is owned by 1,600 members. Many of them live locally, including Patrick Marber, who wrote the play and movie Closer. A few shareholders are famous, notably Nigella Lawson and Steve Coogan. The board of directors is elected by members every year. Community ownership has made Lewes viable but it is no panacea: after a difficult 2014/15, it had to reduce its budget by 33%.

Earlier this season, illustrating the Rooks’ conviction that football can drive social change, the men’s team wore the Gambling With Lives logo on their shirts. As Dobres says: “In a nutshell, we don’t think gambling should be normalised through football, especially for young people.”

With 27 of the top 44 clubs in England sponsored by betting companies, the normalisation of gambling is a serious challenge. Indeed, according to the Gambling Commission, 39% of 11-16 year-olds in the UK have bet their own money in the past year and 150,000 people in that age group are already identified as ‘problem’ or ‘at risk’ gamblers. Lewes’ directors believe that the ubiquity of gambling ads and logos in football shows the game is failing in its duty of care to the community and, in particular, to young and vulnerable fans.

Teams and memes

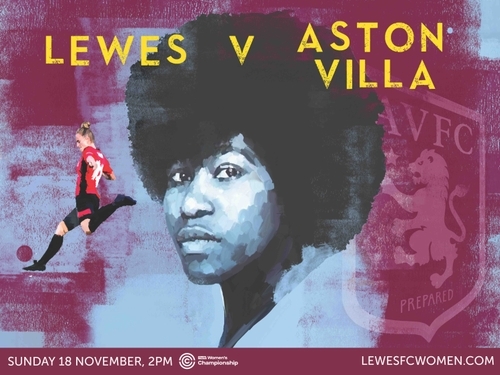

In a much lighter way, the club’s refusal to conform to norms is reflected in the way the Rooks promote matches. The women’s team posters feature a Lewes star, the away team’s colours and a famous woman associated with the visitors’ community – for example, singer-songwriter Joan Armatrading who grew up in Birmingham, starred on the poster when Aston Villa came to the Dripping Pan. The men’s team’s posters riff on everything from popular culture to art and even the local weather (as lone tagline puts it: “In Lewes, the wind doesn’t blow it sucks”). Such memes have also helped the teams acquire significant followings on Twitter, Facebook and Instagram.

In that context, the idea of organising a workshop to help supporters of the women’s team learn how to chant doesn’t sound so outlandish. “Men learn how to chant almost by osmosis from the moment they start going to games as a boy,” says Dobres. “Women don’t.” The initiative is, she says, gathering momentum: “Now that the men’s and women’s veteran teams come to women’s matches whenever they can, one of the male veterans brings along some of the brass band he’s involved with and we all chant together – stimulated by a trumpet and a tuba.”

Like many British women, Dobres grew up abhorring football. In 1995, her future husband Charlie (who is now in charge of the club’s marketing) organised a surprise trip for her to Wembley. Even though England’s men beat the USA 2-0, the fact that a nearby supporter shouted “Get up you tart!” at a player on the ground only reinforced her conviction that football was not for her.

Her Damascene conversion came in July 2017 when she read about the Rooks’ decision to pay their men and women’s teams the same salary. (The players typically earn between £100 and £250 a week.) Astonished that an industry as macho as football was doing something to break the glass ceiling, and intrigued that her local club was making headlines across the globe, she went to watch the women’s team.

Quality and equality

Warmed by a cup of tea and a “palpable sense of camaraderie” among the 120 or so women watching the match, she was inspired by the game itself – and by the idea that women’s football could create new role models who “didn’t look like they’d spent an hour ‘contouring’ before a photo because they had other things on their mind”. (For the record, Dobres was once a fashion model herself, though she gave it up 25 years ago to work as a counsellor and writer.)

Dobres is astonished and appalled that no other club has followed Lewes’ example. The counter-argument, often made by traditionalists, is that men’s football is much more popular than women’s football. There is something in that but, as Dobres says: “Women’s football hasn’t benefited from the same infrastructure and investment that the men’s game has. For fifty years, the FA banned women from playing on FA-affiliated grounds or working with FA-affiliated coaches for, according to Tim Tate in his book Women’s Football: The Secret History, alleged and mysterious ‘gynaecological reasons’. At the time the ban came into force in 1921, women’s football was attracting unprecedented crowds.”

That very unlevel playing field left a legacy that has taken decades to shake off. This year, with almost 12m people watching England Lionesses’ Women’s World Cup semi-final, women’s football finally seems to have reached an inflection point in Britain.

For some diehard male fans, cheering on the Lionesses was as much about quality as equality. The Women’s World Cup demonstrated that the standard of play had increased exponentially. That transformation has fuelled interest – and investment – in the sport.

On the issue of quality, Lewes’ men’s team is perched just below mid-table in the Premier Division of the Isthmian League, the seventh tier of England’s Football League system. Lewes’ women are in a similar position in the Championship, the second tier of the women’s league system. The teams attract similar-sized crowds: the average attendance for the women last season was 586, compared to 624 for the men. The aim, Dobres says, is to show the world that “equality is a rising tide that lifts all boats”. The club is unique in many ways but, like the 5,299 other football clubs in England, it needs to win games to progress.

Looking much further forward, Lewes FC has its eyes on another distinction. “We want to become the most owned club in the world,” says Dobres. That might sound like an impossible dream – “at the moment, we have 1,600 members and Barcelona has 160,000”, she admits – but it reflects the palpable sense of optimism that infuses the club. Directors recognise that they can’t control what goes on the pitch but they can influence everything off it. Besides, as Crystal Palace fan Captain Sensible crooned in his No1 hit Happy Talk, “If you don’t have a dream, how you gonna have a dream come true?”

You can find out more about Lewes FC, become a member or donate here.